A Miraculous Escape From Certain Death in World War II by Reg Barker

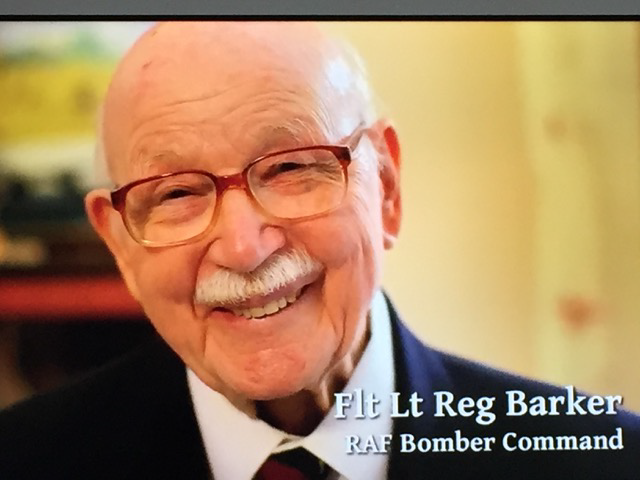

We are delighted to share a wonderful story from one of our clients – Flt. Lt. Reg Barker who has given permission for it to be placed on our website.

We are delighted to share a wonderful story from one of our clients – Flt. Lt. Reg Barker who has given permission for it to be placed on our website.

As told by Former Flight Lieutenant, 635 Squadron, RAF Pathfinder Force – Flt. Lt. Reg Barker.

Can I take you back to the summer of 1944 when, after nearly five years, the tide of war was at last turning in our favour? The Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6th had been successful; our armies were fighting their way across France, and Paris had just been liberated after more than four years under German occupation.

My part in this offensive was as an RAF pilot aged 22; the captain of a skilled and dedicated crew of seven. We were a tightly knit team. As their skipper, I remember how privileged I felt to enjoy the loyalty and comradeship of such an exceptional crew. We were all proud to be flying Lancaster bombers with Bomber Command’s Pathfinder Force, as members of 635 Squadron.

On August 26th 1944, we were briefed to fly that night from our airfield at Downham Market in Norfolk, to attack Germany’s naval and submarine base at Kiel. Heavily defended with searchlights and anti-aircraft guns Kiel was an important target, because enemy submarines were a serious threat to the ships upon which our armies on the continent depended to maintain their essential supplies. We were directed to fly in the first wave of twelve Pathfinder aircraft, two minutes ahead of the Master Bomber, who would monitor the progress of the attack and direct the main force of bombers by wireless.

We arrived at Kiel exactly on time, thanks to the superb skill and dedication of our Canadian navigator, Hannes. He calculated a fresh ‘fix’ of our position every six minutes throughout our flight, a remarkable feat of concentration. This enabled him to give me an adjusted course or speed whenever necessary, to ensure that we were always right on time and on track.

We had a good run into the target, with our painstaking bomb aimer, Brian, carefully directing me as he peered through his bomb-sight, “Left…left…right…steady,” to ensure that he would drop our bombs exactly where they were intended. After he called, “Bombs gone!” I held a straight course in order to obtain a photograph of our aiming point. Brian reported that he was pleased with the accuracy of our bombing.

Now we were on our way homewards, thankfully leaving behind the searchlights and flak which had seemed to fill the sky over the target. I was flying the aircraft in a ‘banking search’, weaving so as to help the crew to keep an extra sharp lookout for enemy fighters who might be waiting to intercept us.

Suddenly there was an explosion, a vivid flash and the aircraft was thrown on its back. I managed to regain level flight, assured the crew that I had control and checked with each of them that they were alright. However, we could see flames coming from the starboard wing. Hoping that an increased rush of air might extinguish them, I opened up the engines to full power, but as we increased speed I felt the control column go slack in my hands and I realised that the cables to the tail plane must have been severed. I could no longer control the aircraft, so I immediately ordered the crew to bail out.

At almost the same moment, the nose of our Lancaster plunged violently downwards and the aircraft went into a steep, spiralling dive. Our four Rolls Royce Merlin engines were now driving us at terrifying speed, vertically downwards towards the earth.

The cause of our predicament, as I learned later from our rear gunner, was that the aircraft had broken in two. The tail plane, with the rear turret, had split away from the fuselage. As the rest of us flew on, Dizzy was left behind without an engine or a pilot!

The cause of our predicament, as I learned later from our rear gunner, was that the aircraft had broken in two. The tail plane, with the rear turret, had split away from the fuselage. As the rest of us flew on, Dizzy was left behind without an engine or a pilot!

He recalled afterwards that finding himself alone in the sky, with the tail plane swishing gently from side to side like a leaf falling, he felt sure that he could descend all the way to earth that way. Fortunately, he decided to climb out of his turret and to use his parachute. He landed safely. Without a tail plane, it was no wonder the aircraft had nose-dived so suddenly and so violently. From our flying height of 17,000 feet, we had plunged in seconds to 13,000 feet. As I was lifted out of my seat by the powerful force of ‘g’, caused by the spinning of the aircraft, I could see the altimeter needle racing round the dial, as it clocked 1,000 feet a second in our headlong descent to earth.

Trapped in our tightly spinning aircraft, pinned hard up against the Perspex cockpit roof, and unable to move so much as a finger, I knew it would only be seconds before we reached the ground. This would be the end. There was no time for my life to flash before me, but a fleeting glimpse of the fires raging below prompted a splitsecond prayer to the Almighty!

As I lost consciousness, I was aware only of the most deafening sound. The blasting and buffeting of the wind through the fuselage, the screaming of the propellers and the roaring and vibrating of the four powerful engines combined into an overwhelming, thunderous, unbearable crescendo of noise. Then – total silence, total peace, total bliss! Instead of a fiery hell, I had arrived in that Heavenly abode which I hoped was my destiny!

However, gradually, the silence was broken by a persistent swishing sound. Then suddenly my sight returned and I realised that I was in the sky, and nearby I could see my blazing aircraft coming down beside me. The ‘swishing’ must have been the wind whistling through my clothing as I hurtled towards the ground. I had no sense of falling, but instinctively I grabbed and tugged my ripcord.

As my parachute opened, I could see trees below me, brightly floodlit from above by my blazing aircraft. Instantly, I dropped into the treetops and my aircraft crashed a short distance away.

Anxious to get to the ground as quickly as possible before I was discovered, I released my parachute harness and climbed down through the branches, landing safely on a cushion of leaves. Overhead, I could hear the main force of the bombers, making their way home to England and, wistfully, I thought of the traditional aircrew breakfast of eggs and bacon, to which they were returning.My immediate concern was to get away from my crashed aircraft, which was blazing furiously close by, with ammunition exploding in the intense heat of the fire. I could see the stars overhead, recognised the North Star, and set off hopefully towards Denmark, a few miles to the north. Denmark had been occupied by the Germans, and I hoped I might meet up with some friendly inhabitants there.

I soon came to the edge of the wood in which I had landed, and I crept along a ditch which ran in the direction I wanted to travel. To my dismay, I heard voices coming from ahead. I might have heard them sooner, had I removed my flying helmet, but I had kept it on because my head was pouring blood (from a superficial shrapnel wound, as it turned out). I hid in the hedge, but it was too late, for the approaching villagers must have seen me silhouetted against the fire.

An excited crowd quickly surrounded me, each and every one of them grabbing my tunic or trousers, holding me as tightly as possible. No doubt this was so that each of them could claim to have captured the English ‘terror flieger’. They were all very old or very young. Although a teenage boy held a revolver to my head with his hand shaking furiously, not one of them harmed me in any way. Perhaps because of my amazement that I was still alive, I felt an overwhelming sense of calm. This contrasted with the understandable agitation of these villagers, who must have been terrified out of their lives as my Lancaster came screaming down out of the sky.

Soon, two uniformed men arrived and I was handed over, to begin a new chapter in my life as a prisoner of war. To my great surprise and joy, in the hours which followed, I met up with our rear gunner Dizzy, (whose brief solo trip flying the tail plane I described earlier), and also with three other members of my crew who had also survived – our navigator Hannes; our wireless operator Dick, and our flight engineer Harry. Each of them described an identical experience to my own: being trapped in the aircraft, blacking out, and then miraculously regaining consciousness

in the sky, just in time to release their parachutes and drop into the tree tops. Unfortunately Hannes had suffered a broken leg and was on his way to a German hospital. He was liberated the following April by General Patton’s army. Harry, Dick, Dizzy and I all ended up in the same POW camp – Stalagluft 1 at Barth on the Baltic coast, and we were liberated by the Russian Army in May 1945.

My greatest sorrow has been the loss of two members of my crew: Brian, our bomb aimer and Taffy, our mid-upper gunner, both of whom are buried in Kiel War Cemetery. Brian had left the aircraft through the forward escape hatch, but just after he jumped, the aircraft made its violent nose-dive. I believe he must have been struck by part of the aircraft and had been knocked unconscious, for he was found in a field with his parachute unopened. Taffy died in the aircraft. Once it started its uncontrolled spinning dive, it would have been impossible for him to extricate himself from his cramped turret. Like myself, he would have been trapped by the irresistible force of ‘g’. After blacking out, he could have known nothing more.

Of the 16 Lancasters dispatched by my Squadron on that fateful night, 3 were shot down, together with their 21 highly trained and experienced aircrew. 12 were killed and 9 of us became POWs. The German authorities later acknowledged the attack on Kiel to have been ‘a very serious raid’ with extensive damage. How did the enemy manage to shoot us down without our having any warning? This was a mystery until years later, when we learned about ‘Schrage Musik’, (Jazz Music) whereby German fighters were able to home in on our H2S radar transmitter, which was housed in a blister underneath our fuselage. We also learned that they had been equipped with upward-firing guns. Unknown to us, these advantages enabled them to position themselves directly below us, where they were completely hidden from our view and where their guns could inflict the greatest damage.

The remaining mystery is how the four of us who were trapped under the cockpit roof could have had such a miraculous escape from certain death, only seconds before our blazing Lancaster exploded on the ground. Perhaps the ‘g’ force created by the tightly spinning aircraft acted upon the combined weight of our four unconscious bodies to cause the roof to break apart and to hurl us into the night sky, where we quickly regained consciousness in the cold night air, just in time to be saved by our parachutes.

After the war, the Irwin Parachute Company presented me with a golden caterpillar brooch. This is a constant reminder that I owe my life to the caterpillars which had spun the silk thread that was used to manufacture my parachute. Over 70 years later, I wear my caterpillar with gratitude and humility.

Reg Barker Former Flight Lieutenant

635 Squadron

RAF Pathfinder Force